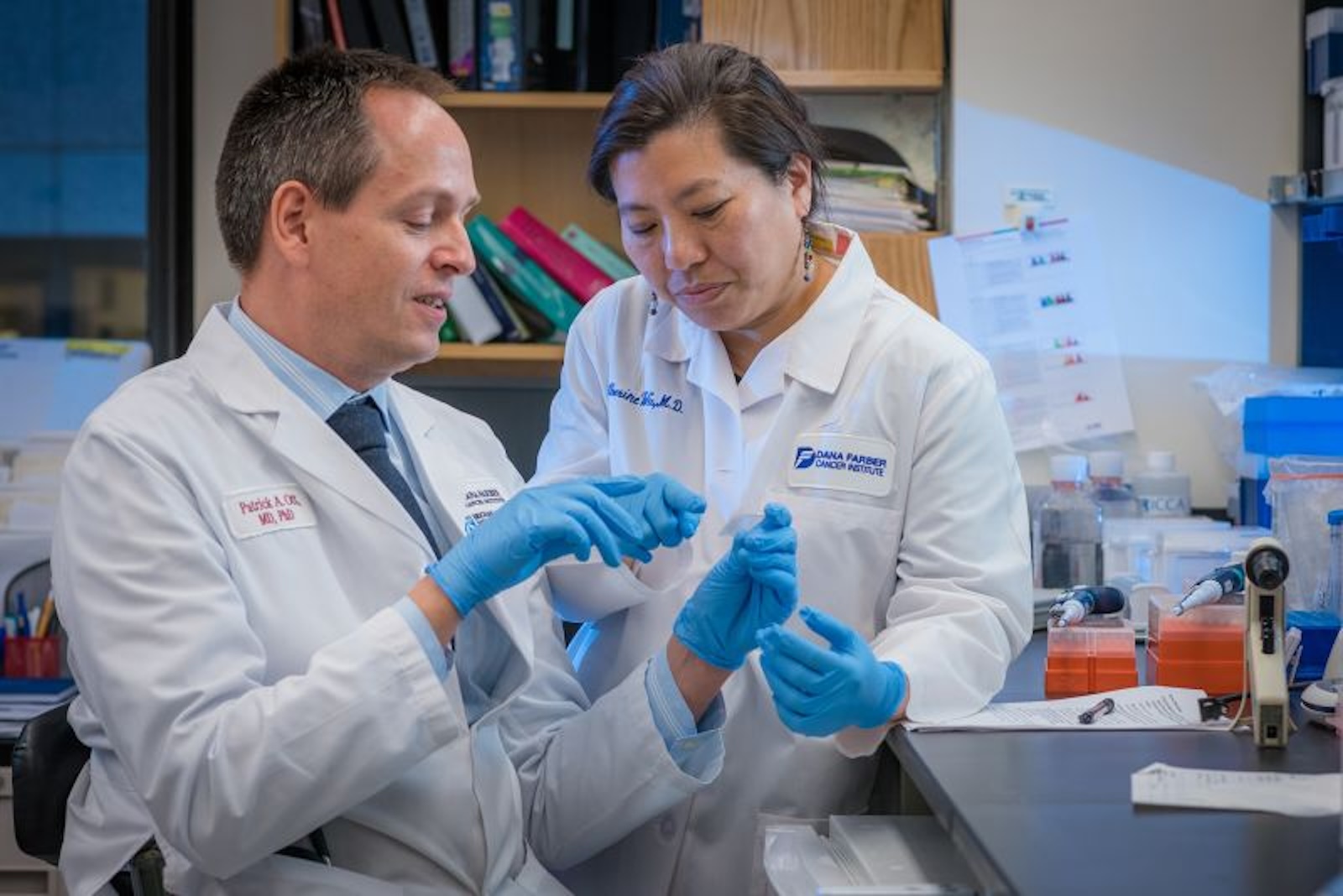

Finding a cure for cancer is a motivating force for many aspiring doctors. There are few who come close to achieving this goal. Among them is Catherine Wu oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston (USA), who has the cancer in view since second grade, when a teacher asked her and her classmates what they wanted to be when they grew up.

“That’s when there was a lot of coverage about the war on cancer,” she said. “I think I drew a cloud, probably a rainbow, and I drew myself like I was making a cure for cancer or something.”

That childhood scribble was prophetic. A search by Wu served as the scientific basis for the development of cancer vaccines tailored to the genetic makeup of an individual's tumor. It's a strategy that appears increasingly promising for some difficult-to-treat cancers, such as melanoma and the pancreatic cancer based on results from early-phase trials, and may ultimately be broadly applicable to many of the approximately 200 forms of cancer.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which selects Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, last week awarded Wu the Sjöberg Prize in honor of his “decisive contributions” to cancer research.

Cancer treatment has “progressed over the years, but there are still many [necessidades] unmet medical conditions for many forms of cancer,” said Urban Lendahl, professor of genetics at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet and secretary of the committee that awarded the prize.

Cancer treatments with “sledgehammers”

The most common treatments for cancer (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) are like sledgehammers, hitting all cells and often damaging healthy tissue. Since the 1950s, cancer researchers have been looking for a way to activate the body's immune system, which naturally tries to fight but is overwhelmed by cancer, to attack tumor cells.

Progress on this front was weak until around 2011, with the arrival of a class of drugs called checkpoint inhibitors, which stimulate the antitumor activity of T cells, an important part of the immune system. The work earned the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine for Tasuku Honjo and James Allison, the latter winner of the 2017 Sjöberg Prize.

These drugs help some people with the disease who had months to live survive for decades, but they don't work for all cancer patients, and researchers continue to look for ways to rev up the body's immune system against cancer.

Wu's fascination with the powers of the immune system came after witnessing bone marrow transplants and seeing how they reset the blood and immune system to fight cancer.

“I had really formative academic experiences that made me very interested in the power of immunology,” she said. “Before my eyes were people who were being cured of leukemia thanks to the mobilization of the immune response.”

Wu's research has focused on small mutations in cancerous tumor cells. These mutations, which occur as the tumor grows, create proteins that are slightly different from those in healthy cells. The altered protein generates what is called a tumor neoantigen that the immune system's T cells can recognize as foreign and therefore susceptible to attack.

With thousands of potential neoantigen candidates, Wu used “extensive laboratory work” to identify neoantigens found on the cell surface, making them a potential target for a vaccine, Lendahl said.

“For the immune system to have a chance to attack the tumor, this difference must manifest itself on the surface of the tumor cells. Otherwise, it would be completely useless,” he added.

A fantastic discovery

The idea of a cancer vaccine has been around for decades. The widely used HPV vaccine attacks the virus that is associated with an increased risk of cancer of the cervix, mouth, anus and penis. However, in many cases, vaccines against the disease have not lived up to their promises, largely because the right target has not been found.

“The ability to identify neospecific tumor antigens has become an important field of cancer research as it offers the possibility of generating tumor-specific vaccines,” said Hans-Gustaf Ljunggren, professor of immunology at the Karolinska Institute, in a video shared by Real Swedish Academy of Sciences. “This is a fantastic discovery.”

By sequencing DNA from healthy and cancerous cells, Wu and his team identified tumor neoantigens unique to a cancer patient. Synthetic copies of these unique neoantigens could be used as a personalized vaccine to activate the immune system to attack cancer cells. Wu and his team wanted to test this technology in patients with advanced melanoma in a clinical trial.

The idea that each patient involved in the trial would receive an individualized vaccine was initially difficult for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates clinical trials, to understand, Wu said. Normally, the FDA would require that vaccines be tested in animal experiments first.

Wu and his team argued their case: “That courtroom was packed. Was the first [julgamento] of that type and there were people from many different offices. Our argument was: 'This is customary, anything we do to an animal doesn't really suit humans, so why go down that path?'”

Once FDA approval was obtained, the team vaccinated six patients with advanced melanoma with a course of seven patient-specific neoantigen vaccine injections. The groundbreaking results were published in a 2017 paper in Nature. For some patients, this treatment caused immune cells to activate and attack tumor cells. The results, along with another paper published the same year led by the founders of the mRNA vaccine company BioNTech, provided “proof of principle” that a vaccine could target a person's specific tumor, Lendahl said.

A follow-up by Wu's team four years after patients received the vaccines released in 2021 showed that immune responses were effective in keeping cancer cells in check.

“I am grateful to all the patients who participated in our study because they are active partners,” said Wu. “It is difficult enough to undergo treatment, but then to undergo a treatment whose benefit is unknown, and to be willing to receive all the extras we need to do this type of research. There are more tests, more blood draws, more biopsies.”

Since then, Wu's team, other medical research groups and pharmaceutical companies, including Merck, Moderna and BioNTech, have further developed this field of investigation, with ongoing trials of vaccines that treat pancreatic and lung cancer, as well as melanoma.

Unanswered questions

All ongoing trials are small-scale and typically involve a handful of patients with advanced-stage disease and a high tolerance for safety risks. To prove that these types of cancer vaccines work, much larger randomized clinical trials are needed.

“The numbers are small, I mean, for obvious reasons,” Lendahl said. “The data [parecem] encouraging, but it’s clear we’re still in early days.”

Scientists are also discovering the most effective way to format vaccines. Wu's team and other groups have used vaccines made from peptides or protein chains. Moderna and BioNtech use mRNA, which the companies pioneered in developing Covid-19 vaccines, to deliver a set of instructions to cells to produce relevant proteins.

“I think there are many paths to Rome. I believe there are many different delivery modalities, but each delivery approach can be optimized in different details,” said Wu. “There has to be investment and how to make this delivery approach work better. And right now there is a huge appetite for mRNA, fueled by our pandemic.”

Cancer vaccines have shown most promise in what oncologists colloquially call “hot tumors,” which mutate quickly, such as melanoma, which was Wu's initial focus. It is unclear whether they will be effective against “cold tumors” such as breast cancer, which are more inert.

“It's easier if more mutations occur spontaneously in the tumor because you have a better variety of potential small molecules to choose from to make your vaccine,” Lendahl said.

Another challenge is how to make these vaccines more cost-effective and faster so they can reach a large number of cancer patients, Wu said. Right now, it can take weeks, if not months, to manufacture individualized vaccines at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars. One active avenue of research is the development of vaccines targeting neoantigens shared by patients with the same type of cancer, raising hopes for an “off-the-shelf” vaccine that many people can use without a long customization process.

Another question is whether vaccines will work better in combination with other treatments to make them a more effective tool, and if so, which ones.

The trial results, published late last year, found that a vaccine, developed by Merck and Moderna, given to patients with advanced melanoma along with a type of immunotherapy called Keytruda, a checkpoint inhibitor-based drug, led to less risk of recurrence or death than those who received the drug alone, the companies said.

It is also unknown at what point in the treatment cycle vaccines will be most useful: treating early-detected cancers, helping patients with advanced disease, or ensuring that patients remain disease-free.

Most ongoing trials involve patients with advanced-stage cancer or in remission, but Wu believes vaccines may be more effective in early-stage disease.

Despite the long list of unknowns, for some involved in these early cancer vaccine trials, the results were life-changing.

“I am very grateful that they allowed me to take [a vacina],” Barbara Brigham told CNN last year. Barbara was one of the patients who received a personalized pancreatic cancer vaccine that BioNTech is testing.

He got to see his oldest grandson graduate from college, a moment she didn't think she would live to see. “The opportunity and timing were perfect,” she said. “It helped me and I hope it helps someone else.”

Source: CNN Brasil

I am an experienced journalist and writer with a career in the news industry. My focus is on covering Top News stories for World Stock Market, where I provide comprehensive analysis and commentary on markets around the world. I have expertise in writing both long-form articles and shorter pieces that deliver timely, relevant updates to readers.